Imagine for a moment, that you’re unemployed. You’ve been traipsing through the Brisbane city for the past few months, walking in to businesses, stores, cafés, just anywhere, applying for countless jobs. You’ve attended listless numbers of interviews, and you’ve been turned by more than you’d like to admit. After all these rebuffs, the day you’ve been grinding your way towards finally arrives- you’re offered an interview for a dream job, one you’re almost overqualified for. You may just take a Tax Declaration Form in with you pre-filled. By now, however, you’ve began to feel pretty hopeless about the situation, and you’ve started to believe that no matter what, you can’t do anything to help your cause. For some reason, you just don’t bother going for the interview at all.

If Martin Seligman were there to make a comment on the situation, he’d declare, “learned helplessness!”.

Above photo: A mighty elephant restrained by a tiny rope and peg

Martin Seligman at a 2004 Ted Talk presetning on Positive Psychology: https://www.ted.com/talks/martin_seligman_on_the_state_of_psychology?language=en

In 1960’s and 1970’s, the American Psychologist and founder of Positive Psychology, Martin Seligman, conducted some famous classic experiment with his colleague Steven Maier involving dogs, and some quite shocking ideas. The experiment set out to demonstrate a concept of ‘learned helplessness’, a concept that is tied into the behavioural and cognitive origins and maintenance of depression. A word of warning: the 60-70’s were a time when cognitive behavioural animal testing was popular, but since then, you’d be stretched to find any psychologists testing with animals in this manner.

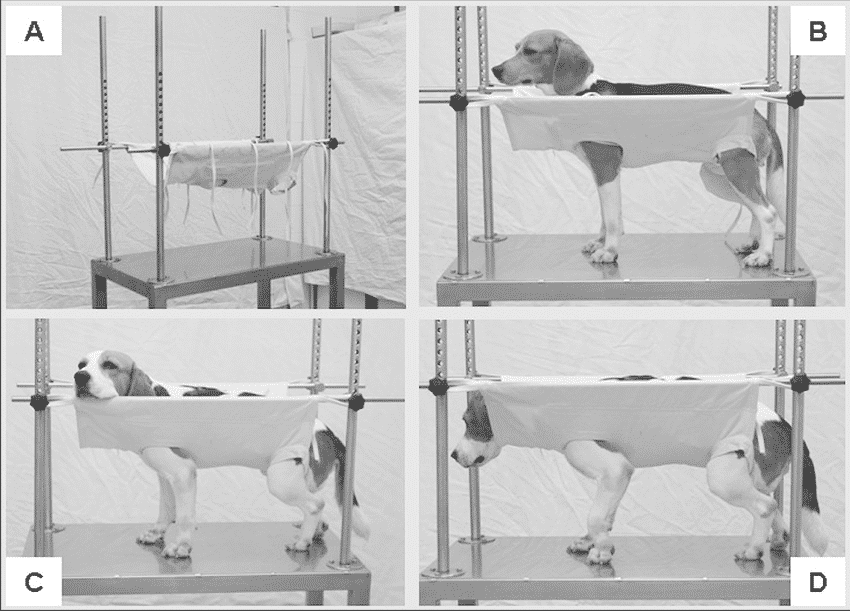

To investigate learned helplessness, in one experiment, Seligman and Maier essentially placed some dogs in a ‘Pavlovian hammock’, which is an apparatus created by another famous psychologist, Pavlov, which restrains an animal from being able to run around as shown below:

They began their experiment by, in Stage 1, sorting dogs into different groups:

– Group 1: Some dogs were placed in the Pavlovian hammock and received shocks from a metal grid flooring that they were unable to escape from, no matter how hard they tried. This is the ‘uncontrollable situation’ group. A disclaimer: these shocks were not painful to the dogs, just not that pleasant to be around.

– Group 2: Some other dogs were strapped into the hammocks and not administered any shocks at all. This is the ‘controllable situation’ group.

– Group 3: The last lot of dogs were strapped into the hammock, and administered with shocks that they could cease by pressing a button with their nose. This is the ‘naïve’ group.

After the 3 groups of dogs completed Stage 1, they moved to Stage 2. In Stage 2 of the experiment, the experimenters all dogs were tested one at a time in shuttle box that delivered electric shocks. A shuttle box is an enclosed space that behavioural scientists used to conduct animal experiments in. This particular shuttle box had a grid flooring that delivered electrical shocks, and that was divided down the middle by a hurdle.

The naïve dogs, Group 3, and the controllable situation dogs, Group 2, quickly figured out that they could jump over the hurdle to the other side of the box where there was no electrified floor. Group 1, the uncontrollable situation group, however, wouldn’t bother to escape the pain. They’d whine, cower, and accept their fate. Those latter dogs had acquired what Seligman coined ‘learned helplessness’.

Seligman found that interestingly, this learned helplessness had a cure which was to physically help the dog over the hurdle. In all, the experimenter would make the dog perform a behaviour until it guided its actions with new cognitions.

But is this the same in people?

Surely, we don’t work on the same cognitive levels as a dog? In 1974, Donald Hiroto took the charge with this last question, and endeavoured to understand its relations to people.

In Hiroto’s 1974 experiment, three groups of people were tested on how they responded to an uncomfortable noise. One group was able to push a button four times to cease the noise (controllable situation), the second couldn’t do anything to stop it (uncontrollable situation), and the last was a control group with no noise (naïve group).

These groups were tested again, but this time, they were all given a new device to stop the noise. The first and last would switch off the noise by simply flicking a lever, but the latter group, who could not stop the noise in the first phase, would sit passively and endure the noise. If Seligman were watching fin on all of this, he’d say “learned helplessness”.

Seligman was left with another question with all of these answers. And that was, ‘why?’. Do we create and idea about ourselves as being incompetent? Do we believe the world as too big and too scary to be challenged? Seligman and his colleagues Lyn Abramson and John Teasdale theorised that learned helplessness is caused by how we attribute things, and that we can attribute things in 3 dimensions:

Put simply:

– Globally or Specific: Attributing things in a ‘Global’ way is seeing our deficits spanning across a broad a range aspect, rather than a specific aspect. Let’s say you went badly on a math test. Global attribution means that you decide this result is due to you being stupid, whereas Specific attribution would dictate that maybe you’re just not that mathematically gifted.

– Stable or Unstable: Attributing things as stable means that when something happens, we are letting it influence out expectations of the past and future. Sticking with our maths example, this is the difference between whether you think you will always go badly in maths tests and always will (stable), or if you think it’s a one off occasion, and you can do better next time (unstable).

– Internal or External: Finally, attributing something that’s happened is 100% your responsibility, versus it being outside you, and because of external factors. So, if you’d failed a maths tests, you’d say ‘I suck at maths’ if it were internally attributed, whereas saying, ‘maths is a hard subject’ would be externally attributing this.

With these pathways of attributing situations, it’s no wonder how we can fall into a learned helplessness. Imagine you’ve been divorced, and you attribute it globally, stable and internally, that’d look like ‘I’m divorced because I’m an unlovable person, I always have and always will be’. How can anyone expect to make a step in a positive direction being guided by such a debilitating and illogical interpretation of reality like that?

The flip side of this would look something like, ‘I know it’s not 100% because of them, but it’s absolutely not 100% me either. This divorce may make me feel awful, but it doesn’t mean I’m an awful person, and certainly doesn’t mean it will always be like this for me’.

Learned helplessness is a cognitive behavioural model of depression, and making a model makes understanding the problem easier, and even better, makes solving it achievable.

Seligman helpfully addresses the prevention and cure of learnt helplessness, and recommends what can be done to prevent and treat learned helplessness within the therapeutic relationship between client and psychologist. Those 4 points, in a nutshell are:

Change your odds. Make changes in your life in maximise the chance of what you want to happen, to happen, and make the bad outcome less likely. Make changes to the bread and butter of your life, the foundations that need to be in order to succeed. Just like in Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, Seligman believes that getting these parts of life in order is crucial.

Make the best outcome not as preferred, and conversely, make the worst outcomes not as horrible. This means to create more realistic goals, so you’re not holding yourself to unrealistic expectations. Seligman also suggests reframing bad outcomes from being dire by assessing the evidence. For example, if you’re rejected by someone you’re romantically interested in, instead of saying ‘I am the most unattractive person in the world’, assess this and replace it with the least destructive conclusion possible.

Make the uncontrollable controllable. Seligman suggests that to avoid and help learned helplessness, we should try to set ourselves up to operate from the most competent position as possible by becoming trained in skills that are necessary, such as social skills, emotional regulation and marital problem solving skills. Taking responsibility for as much as you can means that more of your life is at the mercy of one thing, you, not anyone else.

The difficult problem here is when you do have the skills, but have, well, learnt helplessness, and don’t believe you can achieve anything. Seligman suggests that a therapist can help in this situation by helping modify distorted views of someone’s ability. One of these strategies is changing the attribution of failure away from someone’s inherent ability, but toward their behaviour.

Changing the 3 attribution dimensions towards positivity. Seligman believes it’s important to change how we perceive failure from being stable, global and internal, and to interpret as unstable, specific and external as possible within reason. He also suggests that the perception of success should restructured to be attributed as internal, global and stable.

Of course, all of these steps are much easier said than done. When you’re stuck in a hole such as learned helplessness, sometimes we really need someone to throw down some tools to work our way out. Seligman’s suggestions are directed towards psychologists, and how they can go about aiding their clients.

If you’re feeling like maybe you’re stuck in a rut, and really identify with learned helplessness, our psychologists are rigorously trained in helping exactly that, among a range of other areas.

Sources cited:

Learned Helplessness: Theory and Evidence by Seligman and Maier: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/bd0b/38c23bb66a0762b0023b0306c86411f47edc.pdf

Learned Helplessness: Seligman

https://ppc.sas.upenn.edu/sites/default/files/learnedhelplessness.pdf

Locus of Control and Learned Helplessness, by Hiroto:

http://www.appstate.edu/~steelekm/classes/psy5300/Documents/Hiroto1974-learned-helplessness.pdf

Learned Helplessness in Humans: Critique and Reformulation by Seligman, Abramson and Teasdale

https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/ef52/775276f83a46162a9b364335d9ee5ee73b99.pdf